New York-based African Diaspora Film Festival, in its sixteenth year, took place from late November through to Dec. 14. The following are highlights from the first week’s screenings. To learn more, visit www.nyadff.com.

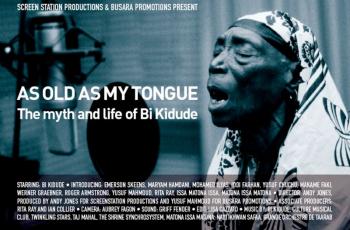

Mark Twain’s classic quote: “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated,” may have become something of a cliché, but Zanzibari vocalist Bi Kidude is certainly entitled to use it. While touring Europe, spurious rumors of her death produced a genuine outpouring of emotion throughout the Tanzanian archipelago. It was yet another chapter in Kidude’s complicated relationship with Zanzibari society, which Andy Jones explores in a documentary profile of the singer entitled “As Old as My Tongue.”

Kidude is thought to have been born sometime around 1915, which would put her near the rather exclusive age of 93. She still enjoys a nice beer and a good smoke, which is frowned upon for women by many of Zanzibar’s Islamists. Kidude also performs without the veil, which is particularly significant. Her musical inspiration and role model Siti binti Saad did in fact perform veiled. For Saad, simply performing in public and recording in India were enough of a challenge to established tradition.

Kidude is generally considered the greatest living representative of Taarab music, a style derived from Eastern African and Middle Eastern musical forms. Its instrumentation includes violins, “ouds,” and traditional percussion instruments, like the “dumbek.” Kidude still interprets the classic songs of Saad, but she also has a repertoire peculiarly her own, like the drinking song we hear at one point.

While she is celebrated abroad, attitudes in Zanzibar seem much more ambivalent. Many come to sponge off Kidude when she returns flush from a world tour, but when the money runs out, so do they. Concerned her music was not better appreciated in her native land, one of Kidude’s most enthusiast fans, Yusuf Aley Chuchu, launched his Heartbeat Studio with a session designed to reintroduce her to Zanzibar. He also explains a certain attitude prevalent among older Zanzibaris, including his mother, that Kidude should retire from music and spend more time at the mosque.

‘As Old as My Tongue’

Mark Twain’s classic quote: “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated,” may have become something of a cliché, but Zanzibari vocalist Bi Kidude is certainly entitled to use it. While touring Europe, spurious rumors of her death produced a genuine outpouring of emotion throughout the Tanzanian archipelago. It was yet another chapter in Kidude’s complicated relationship with Zanzibari society, which Andy Jones explores in a documentary profile of the singer entitled “As Old as My Tongue.”

Kidude is thought to have been born sometime around 1915, which would put her near the rather exclusive age of 93. She still enjoys a nice beer and a good smoke, which is frowned upon for women by many of Zanzibar’s Islamists. Kidude also performs without the veil, which is particularly significant. Her musical inspiration and role model Siti binti Saad did in fact perform veiled. For Saad, simply performing in public and recording in India were enough of a challenge to established tradition.

Kidude is generally considered the greatest living representative of Taarab music, a style derived from Eastern African and Middle Eastern musical forms. Its instrumentation includes violins, “ouds,” and traditional percussion instruments, like the “dumbek.” Kidude still interprets the classic songs of Saad, but she also has a repertoire peculiarly her own, like the drinking song we hear at one point.

While she is celebrated abroad, attitudes in Zanzibar seem much more ambivalent. Many come to sponge off Kidude when she returns flush from a world tour, but when the money runs out, so do they. Concerned her music was not better appreciated in her native land, one of Kidude’s most enthusiast fans, Yusuf Aley Chuchu, launched his Heartbeat Studio with a session designed to reintroduce her to Zanzibar. He also explains a certain attitude prevalent among older Zanzibaris, including his mother, that Kidude should retire from music and spend more time at the mosque.

Although Jones did not capture any truly signal moments in Kidude’s career as they occurred, one could argue that at 93 years of age, give or take, any performance is noteworthy. Jones often shows Kidude still maintaining a solid groove on the hand-drum, despite her advanced age. To her enduring credit, Kidude also remains something of a non-conformist in Islamist Zanzibar, continuing to resist calls for her retirement.

Barely running over an hour, “Tongue” might be brief, but it gives audiences a solid introduction to Taarab in general and Kidude’s music in particular.

“Tongue” also features some compelling music from its subject, even including “Done Changed My Way of Living,” a Taj Mahal track heard over the closing credits, which features Kidude and her frequent backing band, Culture Musical Club. Overall, Jones nicely balances the musical and the sociological in a very watchable documentary.

‘Panman, Rhythm of the Palms’

The drum has always held great spiritual significance beyond its formal music making role, particularly in the Caribbean. It has inspired artists as disparate as Duke Ellington and Vachel Lindsay. The drum’s elemental appeal is deeply felt by the protagonist of “Panman, Rhythm of the Palms.”

The drum in question for “Panman” is the steel pan drum, which originated in Trinidad, but spread throughout the Caribbean, including the Dutch Antilles. It is the instrument that has given meaning to Harry Daniel’s life, but as the film opens, his traditional style of music has fallen out of favor. He labors through a demeaning resort gig, before his deteriorating body collapses, which cues the extended flashback of his musical rise and fall, told through the narration of his estranged student Jacko.

Though fictional, Daniel’s career follows a path recognizable to those who have seen a lot of musical biographies. As a young man, his musical talent initially makes him a star, but his business concerns are damaged by his troubled brother’s incompetence. Along the way, he meets the right woman, but his obsessive dedication to his music leads him to neglect his family.

Oddly, there is not a lot of steel pan in “Panman.” It seems more interested in using the instrument as a symbol—representing both the traditional music losing popularity to modern electronic forms, and African culture, as opposed to the Dutch, which many on St. Maarten persist in identifying with. Fortunately, “Panman” is relatively restrained when addressing issues of cultural identity. (It is considered the first film to be produced by St. Maarten [a Caribbean island], though directed by the Dutch filmmaker Sander Burger.)

As a result, individual drama takes center stage in “Panman,” and to that end, screenwriter Ian Valz is quite convincing as Daniel, displaying both rage and nuance in his portrayal. Frankly, the entire cast holds up well, considering there are not a lot of musical interludes to leaven the script’s trials and tragedies.

Although Valz’s Daniel avoided the cliché of self-destructive substance abuse, there is much in his story arc which seems predictable. In a sense, the lack of faith shown in pan music by the filmmakers undercuts their lionization of Daniel. However, things never get irreparably bogged down in melodrama, and “Panman” does convey a good sense of life on St. Maarten. Highly watchable, it still might disappoint hardcore steel drum enthusiasts.

‘Changing Faces’

Though thought of as an Islamic country, studies estimate roughly forty percent of Nigeria’s population is Christian, so a Nigerian film with Christian themes is not such a contradiction in terms. Faruk Lasaki’s “Changing Faces” suggests personal angels and demons are not simply metaphorical, but wield a tangible influence on mortals which we cannot comprehend.

Marriage means little to Lola, the hedonistic journalist. Unmarried herself, she refuses to let a mere trifle like a wedding ring deter her from a promising sexual encounter. However, the devoutly Christian Dale Svenson takes marriage very seriously. Assigned to cover the painfully dull architectural conference he will address, the uptight Svenson catches Lola’s eye. Over the course of a week, Lola plays an elaborate game of cat and mouse. Eventually, it indeed turns out that whatever Lola wants, Lola gets.

However, this time conquest comes with a price, both for Lola and Svenson. “Faces” posits a world in which a sexual relationship not only occurs on a physical level, but on a spiritual level, involving the spirits people carry with them. By some fluke, Lola and Svenson swap their moral compasses during their night of passion. Now recklessly lecherous, Svenson recognizes something happened to him that night, which threatens to derail his marriage and career. On the wagon and living with integrity, Lola by contrast welcomes her new square life.

While Svenson resorts to a witch doctor’s services in a moment of desperation, “Faces” ultimately links salvation and faith. Lasaki’s debut narrative film, written by Yinka Ogun, is a morality tale in which morality matters. It suggests a life of rectitude is preferable to the ostensive pleasure of sin. However, like Christian films produced domestically, the production values are spotty and the acting is sometimes suspect. British actress Rachel Young fares the best as Lola, the former temptress. Unfortunately, as Svenson, her fellow countrymen, Marc Baylis comes across a bit flat.

Still, in many ways “Faces” is an intriguing film. His scenes involving the unseen “angels” are particularly clever in their staging and Emmanuel Fagbure has a real screen presence as Lola’s leering supernatural companion. It also serves as an interesting reflection of contemporary Nigeria, in that the inter-racial relationships never raise eyebrows—at least for that specific reason. Though undercut by a weak lead, “Faces” suggests Lasaki might have some fascinating films in his future.

‘Return to Goree’

Although it was a small supporting role, Youssou N’Dour showed tremendous screen presence portraying Oloudah Equiano in “Amazing Grace.” A charismatic performer with a powerful voice, N’Dour commands the screen as the subject of at least two recent documentaries: Chai Vasarhelyi’s “I Bring What I Love,” which played at this year’s Toronto Film Festival, and Pierre-Yves Borgeaud’s “Youssou N’Dour: Return to Gorée,” which screened last Thursday at the African Diaspora Film Festival, after a successful week-long run this summer at the late, lamented Two Boots Pioneer Theatre.

“Gorée” seems particularly appropriate for the Diaspora Festival, since it documents N’Dour’s pilgrimage through the music of the African Diaspora, as he leads an all-star group through jazz and gospel arrangements of his Senegalese songs.

The film starts and culminates at Gorée, the island home of the notorious slave-trading outpost off the coast of Senegal. It opens with the stirring lyrics of N’Dour’s anthem “Red Clay,” which speak directly to the African experience, making a fitting start for the musical odyssey to come. After securing the blessing of the curator of Gorée’s House of Slaves for his mission, N’Dour’s first rendezvous is with the French jazz pianist Moncef Genoud, who had previously collaborated with the vocalist on jazz arrangements of his material at a jazz festival. Together they perform with the Harmony Harmoneers at the Greater Israel Christian Fellowship church in Atlanta.

The next stop is New Orleans for a jazz set at Snug Harbor, with drummer Idris Muhammad and bassist James Cammack joining the rhythm section for the duration of the tour. In a pattern that repeats throughout the film, director Borgeaud films N’Dour and colleagues in a scorching rehearsal, and then moves on without showing the actual concert.

The next stop is New York for a session with vocalist Pyeng Threadgill (daughter of the often avant-garde Henry Threadgill) and harmonica player Gregoire Maret, who has played on high profile recordings with the likes of Cassandra Wilson, Pat Metheny, and Marcus Miller. We also hear a jazz-and-poetry collaboration with Amiri Baraka, who is relatively restrained in his militancy on that particular day, mercifully.

N’Dour and company make a final stopover in Luxemburg to add two more axes to the band, trumpeter Erni Hammes and Austrian guitarist Wolfgang Muthspiel. As the musicians assemble in Dakar, the Harmoneers tour the House of Slaves and are moved to sing “Return to the Land of Gorée.” It is a scene that recalls Roberta Flack singing “Freedom Song” in a Ghanaian slave fortress during the “Soul to Soul” concert film.

When the final concert kicks off, it does sound like the band came together into a tight unit. Unfortunately, we do not hear the full group with the Harmoneers or Threadgill. In general though, N’Dour’s experiment sounds great. His songs translate well into a jazz context, helped by the presence of jazz musicians like Muhammad and Genoud who are well attuned to N’Dour’s original music.

With an interesting mix of well-known musicians like N’Dour and Muhammad with European artists largely unfamiliar to American audiences, like trumpeter Hammes in particular, Gorée is definitely a cool jazz documentary.

Friends Read Free